Tobacco has long been a subject of reverence among pipe smokers, celebrated for its rich flavors and contemplative ritual. Yet, beyond the smoky allure of a well-packed bowl lies a dimension of tobacco steeped in cultural and spiritual significance—a side that has sustained the traditions of many Native American communities for centuries. Today, we explore sacred tobacco: its role as the foremost of the Four Sacred Medicines, the historical attempts to suppress its cultural use, and the modern efforts to reclaim its sacred heritage.

The Four Sacred Medicines

In numerous Native American cultures, there exist four sacred plants known collectively as the Sacred Medicines. Tobacco, given by the Creator, holds a place of paramount importance as the primary activator of the plant spirit. Alongside tobacco, sage, cedar, and sweetgrass complete this quartet. Together, they serve dual roles: enriching everyday life and empowering ceremonial practices. Elders often explain that when these plants are burned, the aroma is a gift to the spirits, inviting their guidance, protection, and benevolence.

For Woodland Indians, in particular, tobacco is much more than a plant—it is the vital medium through which communication with the spiritual realm occurs. The Ojibwe refer to the spirits as manidoog, who are believed to be exceptionally fond of tobacco. Whether through the ritualistic offering of dry tobacco at the base of a tree or the ceremonial pinch thrown into water before embarking on a canoe trip, these practices underscore tobacco’s role as a bridge between the human and the divine.

|

| The Peace Pipe by Charles Marion Russell, 1898 |

Sacred Rituals and Daily Life

For Native peoples, sacred tobacco is interwoven into the fabric of daily existence. It is common to find offerings of tobacco at graves, as tokens of respect and remembrance for departed loved ones, and as gifts to elders and healers when seeking their wisdom. During hunts, a pause for a smoke isn’t just a moment of rest—it’s a respectful acknowledgment of the spirits believed to inhabit the land, a request for safety and success, and a token of gratitude for nature’s bounty.

Historical artworks, such as The Peace Pipe by Charles Marion Russell (1898) and later by Eanger Irving Couse (1901), visually capture the profound role that tobacco plays in Native ceremonies and cultural identity. These images remind us that tobacco, in its sacred form, is a symbol of unity, peace, and spiritual dialogue.

|

| The Peace Pipe - painting by Eanger Irving Couse, 1901 (MET, 17.138.1) |

The Banning of Sacred Tobacco and Cultural Suppression

Despite its deep spiritual roots, sacred tobacco—and by extension, Native American cultural practices—faced severe repression beginning in the late 19th century. In 1883, the U.S. government enacted the Code of Indian Offenses, a series of regulations designed to forcibly assimilate Native peoples into European-American culture. This code criminalized many traditional practices, from sacred dances and rituals to customary marriage and funeral rites, effectively targeting the very essence of Native cultural identity.

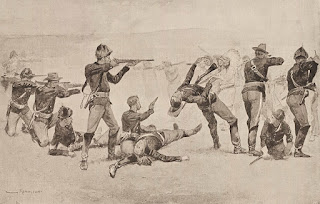

Henry M. Teller, a U.S. senator and former secretary of the interior, was among those who viewed Native traditions as impediments to “civilization.” His influential position helped cement policies that not only banned sacred ceremonies but also disrupted the transmission of ancestral knowledge, including the traditional uses of tobacco. The suppression of these sacred practices, culminating in tragic events like the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890, left enduring scars on Native communities, severing vital connections to their spiritual heritage.

Native Americans were not considered full citizens until 1924, and for decades, religious freedom was narrowly defined as adherence to Christian practices. It was not until the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA) of 1978 that Native peoples were granted the legal right to practice and preserve their cultural and religious traditions.

|

| The opening of the fight at Wounded Knee, Federic Remington, 1891 |

The Encroachment of Commercial Tobacco

As sacred tobacco practices were suppressed, commercial tobacco companies saw an opportunity. With traditional tobacco rendered “illegal” in its sacred form, major corporations began marketing commercial tobacco products—brands like Natural American Spirit, Big Red, and Red Man—to Native populations. These products, derived from Nicotiana tabacum, were markedly different from the traditional sacred tobacco, which is primarily Nicotiana rustica.

Nicotiana rustica, used in sacred ceremonies, grows smaller, has yellow flowers, and is considerably more potent—four to fifteen times more so in nicotine content than its commercial cousin. Over time, many Native communities found themselves replacing sacred tobacco with these mass-produced alternatives. Commercial tobacco not only blurred the lines of traditional practice but also introduced a host of health and social issues that have affected Native populations disproportionately. In many cases, commercial cigarettes were used as a surrogate in ceremonial contexts, creating a disconnect between cultural intent and the reality of addiction.

.jpg) |

| Advertisement: Red Indian Cut Plug, American Tobacco Company, 1900 |

Reclaiming the Sacred: Healing and Cultural Revival

Today, a renewed movement seeks to restore the sacredness of tobacco among Native peoples. Initiatives like the Keep Tobacco Sacred Collaboration are at the forefront of this cultural resurgence. These programs aim to educate Native youth about the differences between commercial and traditional tobacco, teach cultivation techniques for sacred tobacco, and support ceremonies that honor its original purpose.

Native leaders and elders are working tirelessly to reclaim their heritage, advocating for the respectful use of sacred tobacco as a vital component of their cultural identity. In interviews, figures like Native American Sean Brown have described the struggle of separating the sacred from the commercial—a challenge that underscores the profound cultural loss inflicted by past government policies. Efforts are now underway to reestablish sacred practices, offering Native communities a way to heal from the wounds of cultural suppression while countering the aggressive marketing tactics of large tobacco companies.

|

| Survivors of Wounded Knee Massacre, John C. H. Grabill, 1891, Library of Congress |

Conclusion

Sacred tobacco stands as a testament to the enduring spiritual legacy of Native American cultures. It is the first of the Four Sacred Medicines—a gift from the Creator that continues to serve as a medium for connecting with the spiritual realm. Despite a history marred by oppressive policies and the incursion of commercial interests, Native peoples are reclaiming their sacred traditions, one ritual at a time.

By honoring the ancient practices surrounding sacred tobacco, Native communities not only preserve their heritage but also pave the way for healing and cultural revitalization. As we learn about these traditions, we are reminded of the power of sacred plants to foster a deep, meaningful connection between humanity and the divine—a connection that deserves to be respected and preserved for generations to come.

.jpg) |

| A sacred bundle with a medicine pipe of the Blackfoot, 1912 |

Bibliography

- Wenger, T. (2011). Indian Dances and the Politics of Religious Freedom, 1870-1930. Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 79(4), 850–878.

- Rhodes, J. (1991). An American Tradition: The Religious Persecution of Native Americans. Montana Law Review, 52(1).

- Treuer, D. (2020). The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America from 1890 to the Present. Corsair.

- Rules Governing the Court of Indian Offenses; Henry M., edit; U.S. Department of the Interior, online; Office of Indian Affairs; Washington, D.C. (1883).

- Henry M. Teller: A Featured Biography. U.S. Senate: Henry M. Teller: A Featured Biography. (2023, August 9).

- Talbot, S. (2006). Spiritual Genocide: The Denial of American Indian Religious Freedom, from Conquest to 1934. Wicazo Sa Review, 21(2), 7–39.

- Vecsey, C. (1993). Handbook of American Indian Religious Freedom. Crossroad.

- Brokenleg, I., & Tornes, E. (n.d.). Walking Toward the Sacred: Our Great Lakes Tobacco Story.

- Lempert, L. K., & Glantz, S. A. (2018). Tobacco Industry Promotional Strategies Targeting American Indians/Alaska Natives and Exploiting Tribal Sovereignty. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 21(7), 940–948.

- About Keep Tobacco Sacred Collaboration. KEEP TOBACCO SACRED. (n.d.).

- Ahébée, S. (2021, May 14). Sacred Tobacco and American Indians, Tradition and Conflict. WHYY.

- Keep Traditions Alive. Keep Tobacco Sacred. Keep Traditions Alive. Keep Tobacco Sacred. - MN Dept. of Health. (n.d.).

By exploring the sacred dimensions of tobacco, we not only gain insight into the spiritual lives of Native peoples but also recognize the importance of cultural preservation in the face of historical adversity. May we all come to appreciate and respect the sacredness of these ancient traditions as we move forward in our own journeys of understanding and healing.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment